Alternatives to Brainstorming

In our earlier post, To B or not to B…What we Know about Brainstorming, we made two basic arguments. First, we said that the way we typically do brainstorming today—following the common rules—is not the best way to do brainstorming. Second, we acknowledged that not all problems are well-suited to brainstorming, and said we would follow up with a post describing some of the valuable alternatives. Well, here’s that post.

Brainstorming is not Duct Tape

I have a couple of relatives who basically fix everything in their homes, garages and yards with duct tape. The stuff is incredible. In fact, I have a son whose big request for Christmas one year was rolls and rolls of different colored duct tape and all the cardboard boxes that the other gifts came in. He used them to make awesome stuff, like a Captain America shield and a Kingdom Hearts keyblade.

Well, brainstorming isn’t duct tape. It isn’t very good at doing things it wasn’t designed to do. It’s pretty obvious when you put it that way, but you’ve probably had the experience of sitting in a room to “do some brainstorming,” feeling all the while like you’re wasting your time. That’s because the tool is better known than the purpose of the tool.

So, as we kick this off, let’s be clear about what brainstorming is designed to do, and just as clear about what it isn’t’ designed to do.

Brainstorming (when done well) is good for…

Generating possible solutions to non-complex problems (see the previous post for the difference between complex and complicated problems)

Generating a lot of ideas in a short amount of time

Generating a wide range of ideas

And that’s it.

Ok, that’s not quite it. As I said in the previous post, it has some potential “side effects” that can be very desirable as well. These can include team cohesion, building the skill of productive disagreement and debate, and possibly even learning a little humility when experts and non-experts are working on the issue together (I’m speculating on that last one—I haven’t seen any research on that).

Brainstorming is not good for…

Generating possible solutions for complex problems

Actually solving a problem

Choosing between alternatives

Decision-making based on important criteria

Building on previous ideas (Although this is a stated objective or rule of brainstorming, in my experience of watching maybe hundreds of brainstorming sessions, many teams don’t do it very well because “building on an idea” isn’t universally understood and because they’re so focused on not judging ideas they can sometimes feel that building on an idea can include an element of judging. You’ll recall in the previous post that there’s evidence to suggest that withholding judgement during a brainstorming session is bad advice.)

So, given all the things brainstorming doesn’t do especially well, what other techniques or approaches are available? Here are some that fall roughly into three categories: “Tweak the System,” “Tweak the Problem” and “A Whole New System.”

Tweak the System

The first group of suggestions fall into what I’ll call the “tweak” category. In other words, they’re still basically the traditional brainstorming approach, with some interesting adjustments.

Sleep on it. Hold a traditional brainstorming session, write up the notes, distribute the notes, have everyone read the notes in the evening after the session, sleep on it, then each person individually records any new thoughts they have the next morning. Have a follow-up meeting later that day to discuss any new ideas that cropped up.

Walk on it. Similar to the sleep on it approach, but substitute a walk for a night’s sleep. You could do this all in a single day, of course.

Back-and-forth it. Split your brainstorming group into two subgroups and put the subgroups into different rooms. In one room do traditional brainstorming; in the other, participants capture their thoughts in silence. At the end of a specified time (5-15 minutes), each team organizes their thoughts (categorize, eliminate redundancies, etc.) then sends a representative to the other room to share what they came up with. You do a 2-3 of rounds of this, allowing participants to switch rooms between rounds if they wish, then bring everyone together for a final discussion.[i]

Structure your outputs visually. There are a ton of ways to do this, ranging from mindmapping to using a grid to intentionally combine initial ideas. Visual structure can be very helpful.

There are a ton of additional system tweaks on this post: https://clickup.com/blog/brainstorming-techniques/

Tweak the Problem

Oftentimes productive insights and solutions can be found when you think differently about the problem you initially intended to solve.

Reframing—incredibly potent as a tool, reframing asks you to make sure you’re solving the right problem, not just the obvious problem. See the work of Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg for more on this.

5 Whys—made famous by Toyota, you simply move backward from the original problem statement, ask yourself repeatedly (as many as 5 times), “why is that happening?” The goal is to arrive at something more like a root-cause. In fact, this same general approach is sometimes called a “root-cause analysis.”

SWOT analysis—SWOT stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats. The first two are generally associated with issues internal to your organization; the second two are related to things external to your organization. The aim is to look at your company or a situation in your company and ask how that situation creates or contributes to strengths and weaknesses internally and opportunities and threats in the environment. It helps to demonstrate that every organization or issue within an organization has pros and cons associated with it. It also makes it clear that you want to try to solve a problem, perhaps by eliminating weaknesses, without simultaneously eliminating strengths.

You can see that these and similar ways of looking at problems—rather than just focusing on solutions—can open up a huge range of new perspectives. They also point us toward the final category, which is setting up a system that is more structured, more rigorous and takes on much more than just coming up with some good ideas.

A Whole New System

The approaches in this category are aimed not simply at creating ideas, but also at arriving at great decisions. In that sense they far exceed the utility of standard brainstorming, though they also include some very interesting methods of generating ideas. I’m only including two here because I like them best and because including more would change this from a blog post to an ebook. There are lots of variations on these two, and many other approaches that are similarly structured.

Nominal Group Technique

The Nominal Group Technique (NGT) was originally developed in the early 1970s by Andre Delbecq and Andrew H. Van de Ven, and has been used pretty much as designed since then. I’ll mention a couple of possible variations to the stand approach in a moment.

In contrast to pure brainstorming, NGT is a process that includes ideation, but goes on to reach a conclusion or decision. The ideation stage shares a couple of Osborne’s original rules for brainstorming, but the overall NGT process—unlike the brainstorming sessions you’ve probably experienced—is highly regulated, which might be why it is used so little. For it to work, the facilitator of the session needs to prepare well and be very strict about adherence to the process throughout the session.

Like most approaches, people see upsides and downsides to it. On the possible downside, it’s pretty rigid and inflexible, and therefore not usually considered as “fun” as typical brainstorming. It’s not very good for dealing with multiple dovetailed problems. Another drawback for some teams is that this process really should be facilitated by someone who is not part of the process. The facilitator will have her hands full without also trying to contribute on the content. You don’t necessarily have to hire a consultant to do this, but you will want someone who’s good at facilitating teams and holding the line on the rules of the exercise.

On the other hand, that same rigidity is very good at balancing airtime between participants. So, if you’re used to sitting quietly in meetings or brainstorming sessions because “you know who” does all the talking, get ready to finally share all the great ideas you’ve been saving up. Because of the structure, a lot of people enjoy the time-savings that come from traveling down a much straighter line from problem to solution. Plus, this approach has been shown to generate more ideas and a broader range of ideas than traditional brainstorming.[ii]

Here's how it works, in five easy—well, pretty easy—steps. I’ve attached timing to each step, but of course this could vary.

Step One: Setup (Brief)

The facilitator explains what’s about to happen, identifies the problem to be solved and sets the ground rules.

Step Two: Thinking and Writing (about 10 minutes)

This step is done essentially in silence. Each person in the room is given a sheet of paper with the problem or question to be answered at the top of the sheet. You have about 10 minutes to think in silence and write down your thoughts/ideas/answers. This is how the process ensures a wider range of ideas (recall the anchoring problem I talked about in the previous post).

Step Three: Listing (probably 15 – 30 minutes)

The facilitator goes around the room and asks each participant to name one idea or answer from their list. This is not the time for extended explanations, so responses should be as clear as possible. It’s the facilitator’s job to cut off discussions when needed. The listing continues around the room until all the unique ideas have been captured as a master list on a flipchart, whiteboard, etc. in full view of all participants. The facilitator should make sure to use the exact language of the person sharing the idea, or abbreviate it in a way that satisfies the idea’s owner. (If more than one person comes up with the same idea, it is only written once on the master list.) Participants are free to add to their personal list throughout the Listing step if they hear something that inspires a new idea.

Step Four: Discussion (probably 30 – 45 minutes)

Now’s the opportunity for people to ask for clarifications of ideas on the list. Based on my experience and research, there appear to be two general approaches to this phase. I’ll call one the “strict version” and the other the “looser version.”

In the strict version, as in traditional brainstorming, it’s not about critiquing the ideas, but strictly about clarifying the ideas. There may be efforts to identify categories, but you shouldn’t eliminate any of the ideas. Just make sure everything’s clear before moving on to the final step.

The looser version is actually a collection of possible “loosenings.” You could certainly loosen up on some things while remaining strict on other things.

If the group agrees that two or more ideas on the master list are essentially the same idea, you could combine them or eliminate one or more.

If you want to discuss the merits of ideas at this point, you could do that by exploring pros and cons.

If you wanted to add another idea to the list that emerges from the discussion, you could do that.

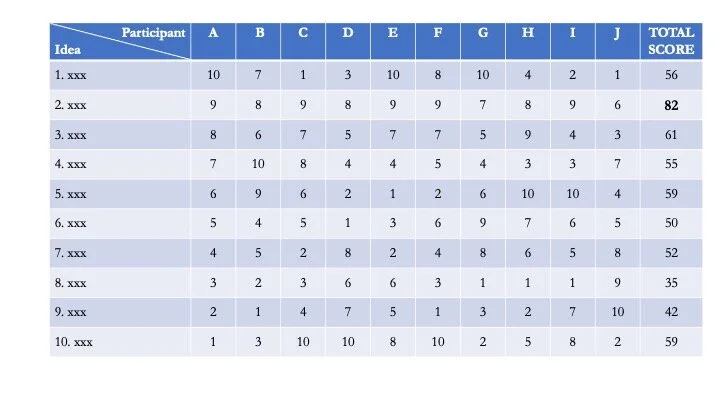

Step Five: Scoring (5 – 10 minutes)

How long this takes depends on the number of ideas you’re working with and how many people are in the room. What makes this interesting—and requires more than 30 seconds—is that it is not simply, “raise your hand for your favorite idea.” Rather, each person in the room rank orders all the ideas on the list from 1 – N (N being the total number of ideas on the list). So, if you had 10 ideas on the master list, each person would rank the ideas from 1 – 10, with 10 being the top score.

Just as in the Thinking and Writing step, Scoring is done privately and individually before the totals are added up. There are a variety of ways to do this, of course, and the approach you choose may be influenced by whether you want to keep the “votes” confidential or not. If you’re not too concerned with confidentiality, you could simply ask each person to call out their rankings and tally them on the flipchart or whiteboard. If you were concerned with it, you could have people submit their rankings to the facilitator who would do the math.

The math works like this: the total score for each idea is added up, and then those totals determine the outcome. So, for instance, if you had 10 ideas and 10 participants, it’s conceivable that all 10 participants would put the same idea at the top of their list. In this case of unanimity, that idea would have a total score of 100, and would be the selected solution. However, and more likely, there’s often some difference of opinion about which idea is best, but more agreement about which idea is second or third best. In a case like that, you might see something like this:

So, although ideas 1 and 10 each received several top rankings, idea #2 had the highest level of consistent support, and therefore came out ahead.

As you can see, this process is much more structured than traditional brainstorming, and might therefore be less “fun” for some people, but it does get the job of ideation done—probably better—and takes you right to a solution. Those are some pretty big upsides.

The Delphi Technique

Here’s another structured approach that involves idea generation, but is predominantly aimed at reaching a conclusion. Unlike Osborne’s suggestion that you bring together a combination of experienced and less-experienced participants, the Delphi approach leans heavily on gathering multiple expert opinions.[iii]

The technique is iterative, and works like this:

Invite multiple experts to provide their opinions/forecasts and—very importantly—rationales on a specific question or issue. These responses are solicited in the form of a questionnaire/survey. The facilitator of the process—who is not a contributor/expert—collects all the responses, anonymizes them, and sends them back out to the same panel for reactions.

Panel members receive a consolidated list of all first-round responses, including the rationales for the opinions or forecasts. This allows panelists to comment not only on conclusions but on the assumptions or facts that lead to each conclusion.

Those responses are sent back to the facilitator for another round of consolidation.

As the rounds continue, the panelists move toward consensus, until—ideally—a final and shared perspective is reached.

The obvious downside to this approach is the amount of time required. The upside is that it moves a group of experts to a shared conclusion. Along the way, it manages to avoid some of the common challenges to convening experts:

Eliminates egos by eliminating ownership—in this format, reputation and seniority have no advantage because no one knows where the idea comes from. This makes it easier for the best ideas to rise to the surface. It also makes it easier for an expert to change her mind without fear of repercussion because no one knows she was the one who changed.

Encourages examining underlying thinking because the rationale for each idea is provided. As anyone who’s ever been stuck in a shouting match (even if it was a very polite, low-decibel shouting match) knows, the argument tends to center around the opinion or the conclusion because we so seldom share our thinking process with one another. The Delphi Technique eliminates that problem.

Consensus-building and merging or improving ideas is the aim of the technique, so likely everyone in the panel will move off of their original thinking in service of achieving the goal. Thus, there is a nice combination of decreasing the pride of ownership and increasing the desire to contribute to the solution. The process works—and the panelists succeed—when the full panel arrives at a shared point of view.

So there you have it. It turns out there are a lot of alternatives to traditional brainstorming. Some of them are just tweaking the tradition to something that works a little better. Some of them are radically different. Which option you choose should be determined by what you’re hoping to accomplish.

And if you’ve got suggestions for other alternatives to brainstorming, we’d love to hear them.

[i] These three approaches are all over the internet, but the earliest source I could find was in a post on FastCompany.com (https://www.fastcompany.com/3069239/brainstorming-doesnt-work-try-these-three-alternatives-instead) by Judah Pollack and Olivia Fox Cabane, the coauthors of The Net and the Butterfly: The Art and Practice of Breakthrough Thinking.

[ii] Taylor, D.W.; Berry, P.C.; Block, C.H. (1958). "Does group participation when using brainstorming facilitate or inhibit creative thinking?". Administrative Science Quarterly. 3: 23–47. doi:10.2307/2390603. hdl:2027/umn.31951002126441i.

[iii] As the approach has evolved, so has the definition of “expert.” For instance, this approach has been used very effectively to develop policy, drawing on the expertise of many categories of stakeholders, including the “average citizen.”